By Khaled Ibrahim, MiReKoc Summer School ‘24 Alumni

The ongoing civil war in Sudan has thus far led over 1.2 million* (official UNHCR number as of September 30th, was 500,000 at the time of writing of the paper) people to seek refuge in bordering Egypt. To the average North Sudanese, this is a logical decision, especially given the country’s strong historical, cultural, economic, and political ties to Sudan and the presence of a large, pre-established Sudanese migrant network (Grabska, 2006). Additionally, at the start of the conflict, Sudanese women, children, and elderly benefited from a joint visa exemption policy between the two countries, which was reneged upon by the Egyptian government in June of 2023 (Al Jazeera, 2023), now requiring all prospective Sudanese migrants to go through an expensive and time-consuming visa application process. Thus, a majority of Sudanese refugees entering Egypt since June 2023 have opted to do so irregularly.

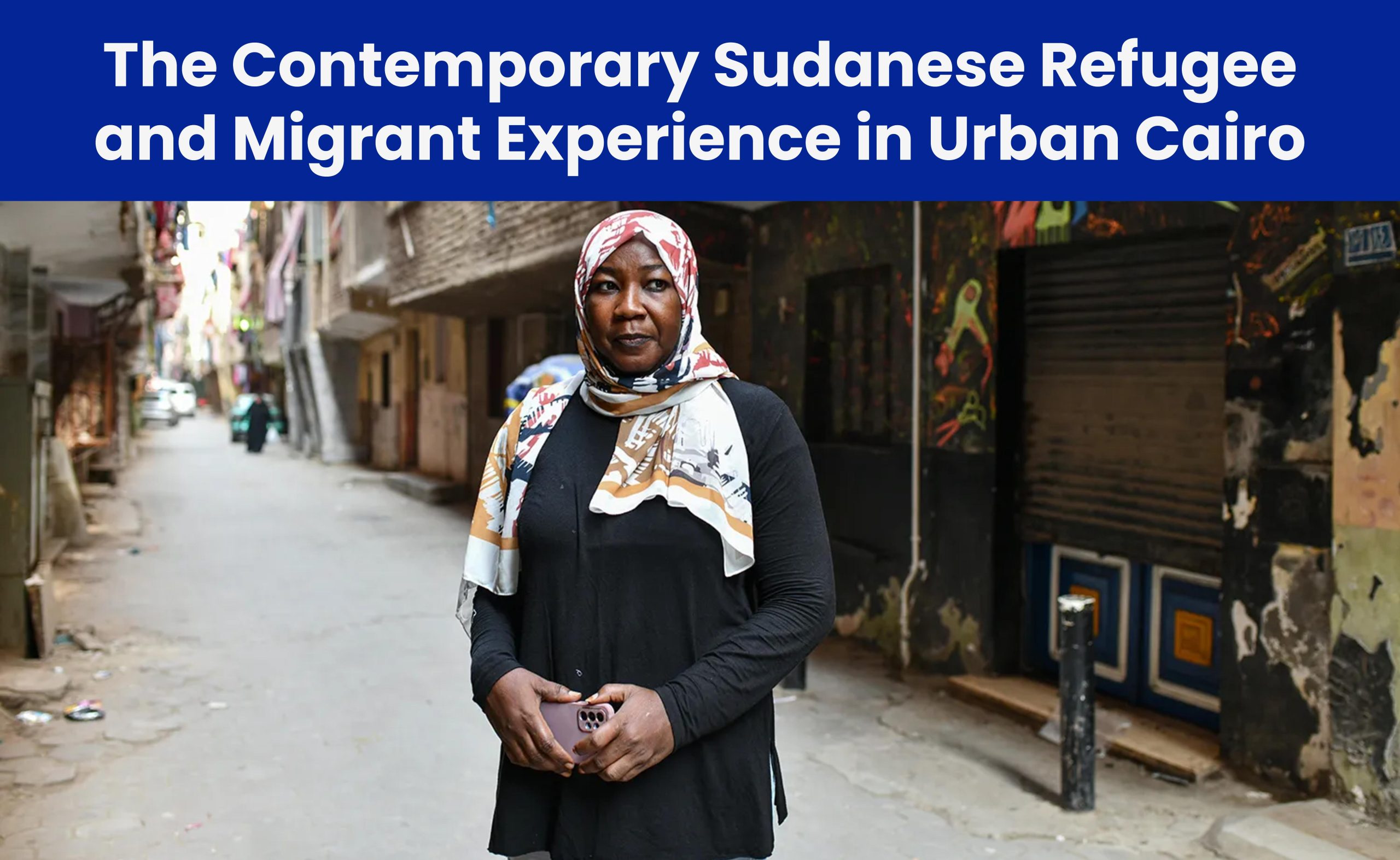

Over a year into the conflict, many headlines have since come out describing the various struggles and human rights abuses faced by Sudanese refugees in Egypt (Amnesty International, 2024). Such headlines are waived off by government spokespersons as mere attempts at defamation. Instead, state officials continue to reiterate that Egypt has welcomed Sudan’s migrants (the state does not automatically recognize them as refugees) with open arms. Thus, the goal of this research is to contribute to the existing literature and help paint a more comprehensive picture of the lived experience of Sudanese refugees and migrants in Cairo through the lens of urban and migration studies.

The insights shared here are the result of a comprehensive review of the available literature on the Sudanese migration crisis and interviews I conducted on-the-ground; I met with five recently displaced Sudanese refugees living in (or having lived in) Cairo and with a Sudanese community leader to discuss their experiences.

It is important to note that Sudanese refugees’ experiences differ greatly according to one’s legal and socioeconomic status prior to and after displacement. Some of the following findings are thus of greater relevance to irregular refugees typically from lower socioeconomic circumstances, who constitute the majority of this migrant flow. Certain issues, however, like discrimination, are experienced by Sudanese migrants in Cairo across the board.

I gained insight into the irregular migration route most taken by Sudanese refugees and the dangers they face along the way, including participant-reported cases of irregular refugee families being held for ransom in Aswan. Beyond that, I was allowed a snapshot of what daily life is like for an irregular Sudanese refugee awaiting their RSD interview; it was characterized by dread, restlessness, and a lack of privacy and security. As irregular migrants cannot obtain a residence permit, and therefore cannot enter into rental contracts, they ultimately tend to stay as guests in crowded housing arrangements that offer little privacy and can induce a wide range of interpersonal conflicts.

The paper’s findings reveal that Sudanese refugees who have settled in Cairo now face a number of challenges including but not limited to: bureaucratic obstacles, wage and rent exploitation coupled with high costs of living (Yokes, 2024), media scapegoating (Muhammed, 2024), and racial discrimination and harassment (Muhammed, 2024) stemming from colorist sentiments deeply embedded in Egyptian society (Sabry, 2021). Most alarming, however, is the indifferent yet arguably hostile Egyptian government policy towards Sudanese refugees that some interpret as an attempt to diminish refugees’ quality of life and discourage future immigration (Dabanga, 2024). One example of such policies is the crackdown on informal Sudanese schools providing education to thousands of vulnerable students who, due to bureaucratic or fiscal barriers, cannot benefit from national or private education systems (Dabanga, 2024). Coupled with reports and participant accounts of racially-biased ID-checks resulting in arrest and even forced deportation (Amnesty International, 2024) and the existence of secret illegal detention centers (Creta & Khalil, 2024), it would appear to some that the average Sudanese experience in Cairo is fraught with difficulties. As a result, the Sudanese migrant network and various NGOs have taken it upon themselves to provide for the refugees’ needs (AFP, 2024). This exemplifies the “humanitarian aid as a form of urban governance” model discussed by Rebecca J. Hester (2024) during her MiReKoç summer school lecture, in which humanitarianism often serves to mitigate harm while reproducing structural inequities and reinforces the status quo of state and city-level uninvolvement.

Finally, the research highlights Sudanese refugees’ extensive engagement in home-making practices, particularly in the Faisal neighborhood of Giza (Osman, 2024). Faisal has historically been home to a large Sudanese and Nubian community that has now been revitalized by the influx of Sudanese refugees and migrants. Many Sudanese businesses and restaurants have opened their doors (AFP, 2024), responding to the needs and wants of the Sudanese populace whilst acting as a place of gathering, networking, and community-building for displaced Sudanese all over Cairo, not just in Faisal. Such businesses also provide numerous jobs for Sudanese asylum seekers and refugees in need of a stable income and help bridge cultural gaps between Egyptians and Sudanese.

—

[1] AFP. (2024, June 2). Egypt’s Sudanese refugees using rich cuisine to build new lives. AFP. https://f24.my/ANGn

[2] Al Jazeera. (2023, June 11). Egypt toughens visa rules for Sudanese nationals fleeing war. Al Jazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2023/6/11/egypt-toughens-visa-rules-for-sudanese-nationals-fleeing-war

[3] Amnesty International. (2024, June 19). Egypt: Authorities must end campaign of mass arrests and forced returns of Sudanese refugees. Amnesty International. https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2024/06/egypt-authorities-must-end-campaign-of-mass-arrests-and-forced-returns-of-sudanese-refugees/

[4] Creta, S., & Khalil, N. (2024, April 25). Egypt’s secret scheme to detain and deport thousands of Sudanese refugees. The New Humanitarian. https://www.thenewhumanitarian.org/investigations/2024/04/25/exclusive-inside-egypt-secret-scheme-detain-deport-thousands-sudan-refugees

[5] Dabanga. (2024, June 27). Egypt suspends studies in Sudanese schools. Dabanga Online. https://www.dabangasudan.org/en/all-news/article/egypt-suspends-studies-in-sudanese-schools

[6] Grabska, K. (2006). Marginalization in urban spaces of the Global South: Urban refugees in Cairo. Journal of Refugee Studies, 19(3), 287–307. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/fel014

[7] J. Hester, R. (2024, June 14). Refugees and Migrants in Paris: Governance, Humanitarianism, and Solidarity. BROAD-ER International Summer School, Istanbul, Turkey.

[8] Muhammed, N. (2024, March 28). How online hate speech fuels anti-refugee sentiment in Egypt. The New Arab. https://www.newarab.com/features/how-online-hate-speech-fuels-anti-refugee-sentiment-egypt

[9] Osman, W. (2024, September 4). My People are Stranded: Bearing Witness to the Struggle of Sudanese Refugees in Egypt – Refugees International. Refugees International. https://www.refugeesinternational.org/perspectives-and-commentaries/my-people-are-stranded-bearing-witness-to-the-struggle-of-sudanese-refugees-in-egypt/

[10] Sabry, I. B. (2021). Anti-blackness in Egypt: Between Stereotypes and Ridicule – An Examination on the History of Colorism and the development of Anti-blackness in Egypt [Master’s Thesis, Åbo Akademi University]. https://urn.fi/URN:NBN:fi-fe2021062940537

[11] Yokes, E. (2024, March 18). Sudanese refugees in Egypt are safe from war, but face dire economic conditions. Foreign Policy. https://foreignpolicy.com/2024/03/09/sudan-refugees-war-africa-egypt-aid-international-community/